In a previous post, I laid out my professional learning objectives for #thisyear. With the first week of school completed, I want to reflect on one:

I will go paperlite #thisyear. I purposefully say paperlite instead of paperless because I recognize that there is value at actually putting pen to physical paper to, for instance, practice annotating a passage, especially when students are tested until at least 2015 on physical paper. Post-PARCC, a completely paperless classroom will make more sense. To clarify, unless there is an educational value to actually physically handing students a paper copy of any document, save test prep as explained, they will access it electronically.

25 iPads for my scholars to use in our IB course.

Because I have a class set of iPads, at the end of the first week of school, I printed 14 pieces of paper, which is in line with the stated purpose of the paperlite classroom.

- 2 copies of each of my 6 class rosters, which were almost immediately irrelevant due to last-minute student schedule changes. 12 pages.

- 2 copies of my schedule to post for students seeking me for help: one on the bulletin board; the other near my desk for my own reference. 2 pages.

In retrospect, rather than printing up the rosters, which were not particularly helpful and I see now were just a kind of back-to-school safety blanket, I would have printed up just a class set of the two documents I wanted students to have before attempting to go paperlite.

I also did NOT print the following:

- A class set (26 copies + 1 for me) of the 7-page IB Learner Profile document

- Another class set of the 7-page IB Language Course A guide

- 110 individual copies of the 1-page IB Learner Profile assignment

- 110 individual copies of the 1-page IB Diploma Programme assignment

- 110 individual copies of a formative assessment asking students to list all 10 traits

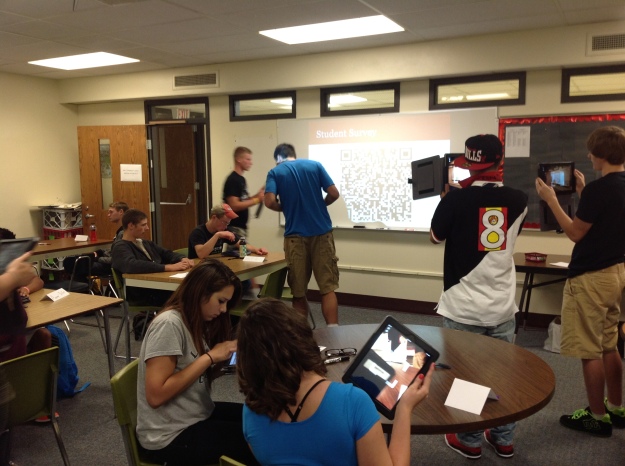

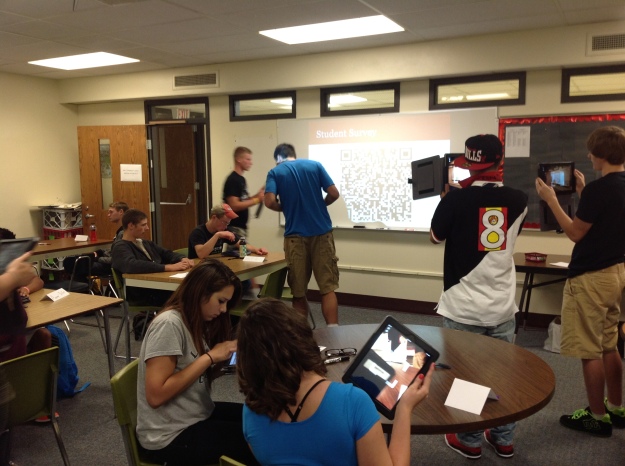

Students in my 6th set class use our iPads to take a paperless assessment.

Total pages of paper saved in week 1? 708!

So, the successes were many.

I saved more than 700 pages of paper. Much of the work this week was effective in establishing the kind of classroom environment and rapport that I expect.

But, I was not successful in sharing two documents digitally with one class. Something went wonky with Doctopus that I was certain had to do with my inexperience with the tool, but try and try and try as I might, I could not figure it out and I could NOT get the documents to the students in my 7th set class electronically.

While I am not pleased that students had a clunky beginning, this failure actually reinforces my resolve that transitioning to an electronic classroom is an important move for me and my students. At the end of my first week, I recognize that what I thought were going to be my own learning goals are intrinsically related to my student learning objectives. What’s ironic is that while the documents I was trying to get to them were questions and prompts about documents about the IB Learner Profile and the IB Diploma Programme, instead they saw someone attempting to be reflective, knowledgeable, principled, open-minded, caring, balanced and a thinker, communicator, risk-taker and inquirer.

I was able to project a copy of the document onto the board, and students were able to take pictures of it and work in another medium: in Notes, in e-mail, on paper if they chose to (about 1/4 did) . After I made sure they had both documents, I let the projector run while I tried to troubleshoot the problem on my own. After about 10 (oft-interrupted to help students) minutes, I realized I could not solve it on my own, and instead checked in with each and every group personally. This gave me the opportunity to personally let them know that I get this week was clunky, that I was extending a deadline for them because of our hiccups, and that I was looking forward to their feedback next week on how the experience is going, what additional hiccups we need to address, and what’s working well for us. It also gave me the opportunity to focus on something other than a malfunctioning script that was making me increasingly frustrated. In a tech-fail, empathizing with students and adjusting deadlines goes a long way.

After touching base with everyone and realizing that sure, they had been exploring the cool new toy that is the iPad we’re using, I also realized they had been hard at work as well. Unfortunately, I’m sure that the experience of having something projected they have to copy down and then complete is not uncommon for them: while I was a fish out of water, they knew what to do. They used their cell phones and iPads and double-deviced it. They created and shared documents with each other they could co-edit, and then used a phone to look things up. They searched Google and found the same links that I did — I thought downloading the documents as PDF files and dropping them in a shared folder was guiding them just the right amount; instead, I found that it was too confusing. They didn’t create the organization system of folders within folders, so they didn’t get it. They don’t use Drive in their budding professional lives, so they didn’t know to search it to find something. While they weren’t able to perform the task in the manner in which I had designed, they were able to perform the task. And I extended the deadline anyway, as promised.

And while they were chatting and working, I sent a Tweet, knowing that a few of the students follow me. It was a kind of note-to-self tweet, something to remind me to work on the “7th set glitch” later this weekend. I intend to unpack for them the work I did this weekend to fix the problem we encountered and provide venues for communicating about tech hiccups that will certainly occur again in our transition to our paperlite classroom. After some Tweets back and forth with Doctopus creator, Andrew Stillman, I found out that my “7th set glitch” was actually a global glitch due to an unprecedented spike in Doctopus usage with more than 10,000 requests per day. He had already fixed the problem and published information explaining it, and nonetheless, he responded to Tweet after Tweet, urging teachers like me to get back to him immediately if his fix didn’t address the situation. It did, and I have already sent out Monday’s classwork via Doctopus.

In addition to the real-world learning that I demonstrated for my students by troubleshooting the glitch, I have further validation from students that this transition is valuable, despite the growing pains. At 9:35 Saturday night, after sending Monday’s work via Doctopus successfully, I got an e-mail from a student clarifying if it was weekend homework or not. I wrote her back at 9:45, and at 9:50, I got this response, which I’ve already starred for my “I need a pick-me up today” folder…

Thanks so much! I love being able to communicate so quickly 🙂

See you Monday!

I thought that e-mail was going to win the night owl award, but then I woke up this morning to another e-mail, sent at 2:16 am responding to the 1-minute long how-to-access-your-Google-account-from-home video I made Saturday morning after so many asked me Friday in class (I know…). This student’s e-mail indicated he had indeed been able to access his account, as he was quoting the assignment and asking for help locating resources to look up the answers, in true Common Core style. By 9:42am I had responded. And then there was evidence that two siblings were already on Infinite Campus checking their grades — this e-mail alerted me to a Gradebook set-up error that has also been corrected.

At the end of my first week experimenting with a paperlite instructional environment, I am confident that this is a valuable transition for both me and my students. We learned that, though not everything will be perfect, by seeking help from those farther along than we, we can accomplish our goals.